The only thing better than listening to a well-loved album is getting to peek behind the proverbial green curtain at the operators behind the tunes. Those “director’s cuts” takes on the creative process, the ways in which musicians collaborate, whether or not lyrics are intentionally written to derive meaning. You know, the gossipy stuff most listeners won’t see.

My partner is a musician, a skilled bass guitarist, and he’s told me a few times that he works better and more creatively when there’s someone else there to play with. Another guitarist, a drummer, someone. Music is conversation, and it’s in the conversations among band members that group identity is formed. It’s where collaborative creativity comes from.

I grew up with parents who listened to glam rock and hair bands more than anything else, at least during my formative years of the early 90s. Mr. Big, Ratt, Cinderella, Motley Crue, Def Leppard, Scorpions, AC/DC, and Great White were but a few bands that made their ways through my musical education. Naturally, Aerosmith was a household staple.

That rolling lick of the titular track of Toys in the Attic? I’ll never not know where that riff comes from.

To understand how quickly the song itself came together, in Tyler’s words, is nothing short of impressive and is a process I’ve seen over and over again when the passion of a thread of music pulls together all the musicians in a space until the weaving is done, the track is finished, and everyone is at once riled up and exhausted.

But watching musicians work together isn’t always sunshine and rainbows, and because people are people first, creative minds second, it’s sometimes the rainclouds, those interpersonal storms, that produce some of the most honest and authentic tunes.

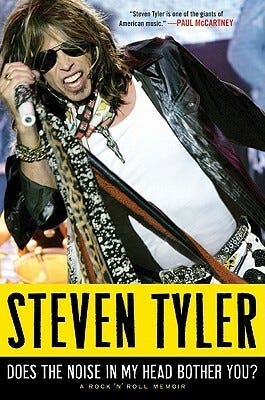

Steven Tyler shared several tidbits within the pages of Does the Noise In My Head Bother You? that musicians (and writers, too, in all honesty) will recognize as words of wisdom, even if they feel a little harsh. But then, no prudent creative person will assert that the process of creating art is easy or without harshness.

Here are selected words of wisdom I hope will pique your interest and show why this memoir is a solid one for understanding group dynamics and the good and bad that happen when a bunch of people work together in creative capacities for extended periods of time.

“Mutual animosity is a necessary part of a band’s chemistry. It’s all egos anyway. Would you want to be in a group who were all clones of yourself? Pretty much anyone who wants to be a rock star is by definition a raging narcissist—then just add drugs!”

I read the first sentence of this selected quote to my partner. He looked at me and said, “Yup.”

There’s something about disagreement, animosity, that really stokes the passion fires and brings the heat into a relationship. And when you have a handful of musicians, all of whom desire fame, clout, respect, or some related outcome, egos clash often. While I can’t speak on the drugs bit since none of the band members in my partner’s space use anything other than cannabis, it was clear from Steven Tyler’s account, what comes when you add drugs to raging egos. It ain’t pretty.

“There are four elements to writing a song, or as they say in comic book land . . . the Fantastic Four. If you break it down, there’s melody, words, chords, and rhythm—put those down in any order and you’ve got something you can play to piss your parents off.”

I loved this succinct little write up the elements of a song because, since I’m a story developer, I think about the component parts of creative works probably more than any reasonable person does. In stories, the breakdown is a little different: structure, character, plot — the Three Musketeers, perhaps, rather than the Fantastic Four. And while most of the authors I work with aren’t exclusively trying to piss off anyone, writing authentically, producing art, generally means someone will be salty.

But as the marketing gurus say ad nauseum: “If nobody hates you, nobody can love you either.”

I also think about probably more than I should, but here we are.

“Watching whales breech; holding a baby bunny; getting a new puppy for Christmas . . . that feeling of GREAT. It’s all humans really want. They say in every moment, you have a choice to make between fear and love. I believe that. But all we really need at the end of the long and winding day is to be petted, to climax, to make love, and to be happy. And that is euphoric . . . with or without the hash coffin.”

When I was a kid, I was convinced I wanted to be a rockstar. I wanted to be on stage with my band behind me, dance around, connect with the audience, croon. This was nothing more than a fantasy, given that I have some serious stage fright and I’ve never really put in the work to become a great singer or musician of any kind. Playing alto sax in the high school band isn’t exactly how one launches a rockstar career.

What I was really looking for was that feeling of greatness. (And isn’t that the folly of many teenagers and young adults, trying to become great, rather than being themselves and stepping into their greatness? But I digress . . .) I wanted to be somebody, to feel something, to share in an enlightening experience with likeminded folks.

I wanted to be happy. Now, being 37 and having learned a few things, I know that happiness is fleeting; contentment — with oneself, one’s family, one’s stations, and more — is the real sweet spot. Happiness is a fickle thing that will fuck off the moment a frustration or pressure point presents itself and sideswipes our plans.

But contentment? That’s the real ride-or-die emotional friend that allows one to live their best life.

“If you want to control people and you know they’re weak, you give them money! Trust me when I tell you that.”

I think about money often; every business owner does. Money coming in. Money going out. Money I have. Money I don’t have. Money I wish I hadn’t spent. Money I wish I could spend. I know we all want security, but money is a false security friend. It makes us feel good in the moment because we can buy stuff. But buying stuff is not a replacement for joy. It’s not a replacement for quality. It’s not a replacement for experience. It’s not a replacement for relationships.

While I’ve said before and will likely say again that there is a certain amount of money one usually must have to feel secure, money in a vacuum breeds greed, resentment, possession, and fear. Too little and we clamor for more. Just enough and we fear misusing it. In abundance and fear losing everything.

Money is the true opiate of the masses, and as long as the feds control that money and can print it whenever they damn well please while devaluing the dollar for the rest of us, I fear money will continue to control us.

“The problem is that rock ‘n’ roll is a fantasy life and part of that fantasy is being high. Like most rock stars I suffer from Terminal Adolescence. I’ll never grow up. The animated twelve-year-old thing—without that you wouldn’t get up onstage in the first place. In rock you never have to grow up because you’re so insulated, you never have to deal with anything.”

The idea of terminal adolescence fascinates me and has since I became a mom. You see, I, too, once felt I’d never grow up, that I could be young forever. And then I grew a human being inside my body, reconnected to my Mother Earth spirituality, and understood the awesome value of adulthood. I grew up, fast. But my musician partner?

He’s a grown-ass adult, but his growth looks different from mine. He’s become possibly more of himself, while I’ve become a different version of myself. He still battles stage fright, but he’s been playing onstage for so many years that nobody notices the limiting beliefs he battles, the concern that folks may not like his tunes, that the crowd just won’t show up. He’s twelve years old again each time he takes the stage.

I feel that way, too, every time I share a piece of writing with the world, be it a book sent back to an author, a DIY story development manual constructed for an author, a blog article written for MetaStellar magazine, a newsletter, a social media post, even these brain-dump book reviews.

While I disagree with the sentiment that you never have to grow up in rock because you’re so insulated, I understand why Steven Tyler qualifies his experience in this manner. Aerosmith was fairly unknown until suddenly they were a household name. And to be jettisoned into stardom does come with its own social insulation as you move from the care of your family into the care of an industry. (Which is frightening to think about, in practical terms, that one could be in the care of an industry. Probably my anti-institutionalization brain leaking in, but here we are.)

“Songs are nothing but air and emotion, but they have intense effects on people’s lives. When people relate passionately to a song, all that goes on in their lives gets attached to the song—and the music never stops.”

If you replace “songs” with books” and “music” with “storytelling",” this sentiment also extends to writers. Books are just strings of letters structured into chapters, but a good book can change the reader’s life for the better when said book punches the reader right in the blood-pumper.

In the same way that certain periods of my life come with their own soundtracks, those same periods come with their own bookshelves and movie recommendations, too.

Dinotopia Lost by Alan Dean Foster nestled in nicely with Jurassic Park and Hanson.

Twilight by Stephenie Meyer snuggled right up to The Dark Knight and All That Remains.

And so on and so forth. Whether one’s creative outlets are in books, movies, tunes, crafts, food, or something else, art has a way of transcending the mundane and taking on a life of its own, even in memory.

Does the Noise In My Head Bother You? made for a fantastic addition to my pragmati-learning reading selections list for the value of opening up group dynamics, exploring the emotions that come at various stages of the artist’s journey, and showing the soft white underbelly of what it takes to stop giving a fuck about what others think of you.

Steven Tyler and Aerosmith became household names expressly because they were determined to make good tunes, rather than marketable ones. They said fuck-off to manufactured work and opened up their creative selves to each other, even when it was hard, for the pursuit of beauty in art.

While it is clear within the pages of his memoir that Tyler still carries with him some hurt feelings, his is a life many dream of living, and you’ll get a dose of what that life looks like should you step inside his head space.

Have you read Steven Tyler’s memoir? If so, what did you think of it?

Your story pal,

Fal ♥

I haven't read the memoir, but I can relate. Particularly to the partner in Terminal Adolescence. The irony is that I was that same terminal adolescent (I just want to write. Bills are for the birds). So, I get the draw to remain isolated, safe from the weird mechanics of the world. But, I know just who to recommend this book to for sure! And will put it on my own TBR as another step in understanding the man I married. :-)