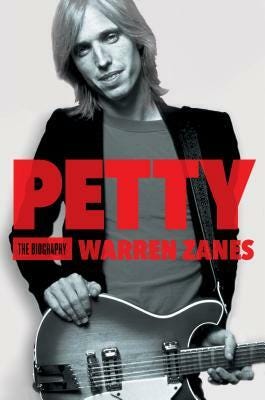

Petty, The Biography by Warren Zanes

Book talk & a masterful command of story and intentionality of language

Celebrity biographies have never been high on my TBR list. While I appreciate what a great number of celebrities have done during their careers, either for their industries or elsewhere, spending too much time with famous people takes the panache out of the day-to-day. That and the fact that celebrities (who are mostly not writers) seem to be able to sell their books to their picks of the Big Five publishers while the rest of the very talented author pool gets crumbs, or worse, can make the blood boil if one focuses on it for too long.

Still, research calls.

Writing a novel isn’t easy, and there are many things to handle with care and balance to write the kind of immersive novel readers want to read.

In alignment with the pragmati-learning process of reading better to write well, Petty: The Biography by Warren Zanes was my number-three pick. And I’m not upset about it.

When I cracked open the cover, I was immediately swept into the work by Zanes’s writing prowess, a writer with a masterful command of story weaving and intentional language.

Interestingly, at least to me, however, is that much of what I am taking from this biography for my own novel is not Petty’s experience as a musician, though I learned quite a bit. Rather, I’m taking away the experiences of folks quoted within the book.

Here are selected quotes from Petty: The Biography for you to noodle over.

“Through the freak we derive an image of the normal; to know an age’s typical freaks is, in fact, to know its points of standardization.” — Susan Stewart

I don’t know how I wound up being lucky enough (or intuitive enough) to read Keefe’s Empire of Pain, Taylor’s The Last Asylum, and Zanes’s Petty: The Biography all in one six-month stretch, but I was. Though these books vary in substance and style and are wildly disparate as far as companion books are concerned, all three carried a thematic thread of crazy/weird/abnormal as one’s failure to adhere to someone else’s definition of “normal.” This is, of course, a painfully human and anti-diversity reality.

Is the tide changing though?

I’m an elder millennial, and I remember when filtering tools for photos became social media standards, not just reserved for those who ponied up the dough for Photoshop. Before that, photographs were full of blemishes, imperfections, and all kinds of other things we could look back on with nostalgia or embarrassment, sometimes both.

When I was in those strange and awkward middle years, the stretch of growth and development that occurs from approximately age 10 through age 16 or so, I was highly impressionable, often depressed, and hid behind too-large clothes because my body didn’t feel like mine. Again, this is totally normal.

Puberty is a time when the body grows faster than the brain develops, and it’s uncomfortable; many folks have stories from this time in their lives because it was a time when both patience was thrashed and resilience was tested.

We wanted to grow up now, to step into our shiny new adult bodies, to have the intellect and experience necessary to navigate the world in our new skins.

Kids these days, though (how’s that for fuddy-duddiness?), are de-filtering their lives, showing their clogged pores, talking openly about their emotional distresses, and more. And while there is a whole separate conversation I’ll reserve for another time about the differences between real life and one’s online persona, I also see a renewed appreciation, in some spaces, for real diversity. And I look forward to the new renaissance.

For Evelyn, the main character in my novel, the idea of the “freak” is one that stays fairly top of mind. Though she’s not going through puberty and is, in fact, about a decade post-puberty, she is going through a transformation of the self of a different kind.

She’s unsure of herself, lacks confidence, and fears rejection in a big way. For these reasons, it’s easier for her to remain on the sidelines than to step into any spotlight so as to remain “normal,” though she feels anything but normal. She doesn’t want the standard outcome but doesn’t really understand how to move beyond social standards to craft her own performance metrics that matter to her. She doesn’t understand her own definition of success, a major learning trajectory arc for her through the novel.

*

“One could say that whenever one is in a group one has to hide one’s best nucleus, or very rarely let it come out. One has to draw a veil over a part of one’s personality.” — M.L. von Franz

I loved this quote from M.L. von Franz, and as I shared in yesterday’s MetaStellar writing advice column, “There’s a difference between one’s individual identity and one’s identity as part of a collective, something Evelyn must contend with as she walks along her growth path to self-discovery.”

When operating as part of a collective, the needs of the collective are promoted and prioritized before the needs of the individual, which means that collectives are often not much more than boxes out from which one must burst if one expects to do something different. However, when one’s livelihood depends on such boxes, the bursting must be stopped lest the container itself falls apart to the detriment of all within it.

In the context of a solo musician vs a musician operating as part of a group, this quote gave me some much needed brain space to work through the group politics at play in my novel. While I had a clear understanding of the individuals behind the group, I was missing that all-too-critical group experience, the arc of the band as a whole beyond the goals of the individuals members, something I touched on briefly in the book talk about Kim Gordon’s memoir.

*

“The human condition is the same for everyone,” says Olivia Harrison. “But once you’re isolated, it’s even worse. When those big life events happen, you can’t see your way out of them. When you’re in the world, you have outreach. When you’re in a bubble, how do you see outside of that? How do people get it? And then you feel like you really don’t want people to see what your troubles are, you’re so private at that point. It’s really easy to not get help.”

Isolation is a pervasive problem and one that has had a light on it since The Event That Will Not Be Named of 2020. Yes, the human condition is the same for all. None of us get to decide when we arrive on this pale blue dot, and the only real certainties we have in life are being taxed to oblivion and dying. And some folks fight against end-of-life rights because of chaotic shortsightedness.

For band politics, isolation occurs when one member’s success begins rising faster than the group’s success, which can cause hurt feelings and natural self-isolation. This is what happened to Petty in some ways, as his name started filtering into households and The Heartbreakers balked against being left behind or referred to as “Petty’s band.”

Evelyn will see this play out for her boyfriend, the vocalist of the band. He wants to be famous and isn’t shy about that desire. He’s also not shy about stepping on toes, even breaking a few digits, to get to that coveted level of fame, though he expects everyone else to do the work necessary to launch his career into the atmosphere.

But being a household name isn’t all sunshine and rainbows.

On the way to the top, one battles the fear of the climb, of failing. After one reaches the top, one battles the fear of falling, of obsolescence. I think about this often, from an existential perspective, because so much of life seems to be avoidance of fear or leveraging fear for growth.

Maybe the meaning of life itself is being afraid and doing shit anyway because humans.

*

“…I guess I have to believe that the best marketing tool is still a good song. And that it’s probably better that I put my time into writing one of those than learning how to do social media properly.” — Tom Petty

I love this sentiment for so many reasons, not least of which is the idea that the best marketing for one’s art is the art itself. Donald Maass, in his non-fiction book, The Fire in Fiction, talks about the best marketing for the next book being in the back pages of the current book. For creative folks who shy against “marketing,” “personal branding,” “networking,” and other -ing buzzwords, the message is welcome.

Making good art means not giving a fuck what others think of you.

It means not wasting precious time talking about art instead of creating art.

It means crafting emotional experiences audiences crave, share in, believe in, wholeheartedly, and with abandon.

Whether the artist writes songs, films, or stories, whether they draw or paint or capture beautiful moments in photos, creators create first and foremost.

Petty put all his energy into creating good tunes. He wasn’t worried about social media algorithms, bot-pleasing, audience-building, or what platform was going to skyrocket his career. And in case you’re racing to point out the anachronisms there, Petty also wasn’t interested in magazine interviews, music videos, and other art-adjacent activities. Instead, he focused on the music itself, on writing, on playing better, on telling song stories regular people needed to hear.

There’s a reason Petty is a longstanding household name while manufactured pop groups were birthed and died out with relatively little fanfare. I mean, do you remember groups like LEN, Jimmie’s Chicken Shack, Powerman 5000, or Harvey Danger? And if you do remember these groups, can you name more than one song written and performed by them?

In my novel, one of the band members, the bass guitar player, is actually a musician for the sake of writing good music. Fame is the least of his concerns; he wants real connections with real people vibing to the same rhythm in a shared space. Where Evelyn’s boyfriend is looking for cash and clout, the bass player seeks creativity and prestige in his craft, the aforementioned Donald Maass’s status seeker-VS-storyteller dichotomy. This is a motif throughout the novel and a concept I’ll pull apart and question through the writing.

Zanes’s Petty: The Biography was a fantastic addition to my curated selection of books chosen for their research value. If you’re writing about being famous, being a musician, or handling individual-vs-group dynamics, there’s much to glean from these well-crafted pages.

Having grown up listening to Petty’s music made the book that much more special, but it’s a well-wrought piece of writing even if you’ve no idea who TF Tom Petty is.

What are you reading to write better?

Your story pal,

Fal ♥